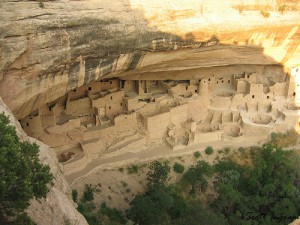

Scott Ingram Photography, Flickr

- Recent town of Vail community survey identifies parking as top issue for townies

- Vail Christian High School board buys back bonds, rescues next school year

- Vail Resorts to host Lindsey Vonn celebration in Vail Wednesday, March 31

- Vail Resorts Epic Pass, Summit Pass available through November 30, 2009

- 9 candidates, including 3 incumbents, running for 4 Vail Town Council seats Nov. 3

- Nominating petitions for four open Vail Town Council seats available Sept. 14

- Eagle County commissioners to vote Tuesday on temporary marijuana dispensary regulations

- Vail Town Council rejects ballot question to change council terms

- Polis defends health-care reform at packed town hall in Edwards

- Vail blaze illustrates need for defensible space, roadless rule changes, state says

- All Real News Articles

November 23, 2008 — Great Smoky Mountain National Park and the mountain range it protects were named for the natural fog that often enshrouds its peaks on the North Carolina-Tennessee border. But in recent years the nation’s most visited national park is called “Great Smoky” for another reason.

“Looking at the East is instructive,” said Mark Wenzler, director of clean-air programs for the nonprofit National Parks Conservation Association. “It’s polluted mostly because you’re downwind from massive numbers of coal-fired power plants, and I think there’s an opportunity in the West to avoid those same mistakes and protect these kinds of places.”

Wenzler was referring to both Great Smoky and Shenandoah National Park in Virginia, where haze from power plants has been obscuring views and degrading air quality for decades.

A proposed Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) rule change revealed by The Washington Post last week would relax air-quality testing standards near the nation’s national parks, including several in Colorado, Utah and Wyoming.

“If you want to be like the Smokies or Shenandoah, then go ahead and build all those plants, but it’s not too late to protect those places,” Wenzler said.

As examples of likely pollution producers, he cited the proposed Desert Rock plant in northwestern New Mexico, which could impact air quality at Mesa Verde National Park in the Four Corners region of southwestern Colorado, and the proposed Bonanza Power Plant in northeastern Utah, which could increase pollution levels at Capitol Reef National Park.

“When you take your family for a hike you don’t expect your kid to have an asthma attack, or when you climb to the top of a peak you want to be able to see the beautiful surrounding scenery and not have it be blocked by haze,” Wenzler said.

“We’ve got a lot of work to do just to clean up the existing pollution. We’d be going backwards instead of making progress.”

According to the Post, the rule change, which would take spikes in energy demand out of the calculation for air-quality violations, is quite controversial even within the EPA. Region 8 Acting Administrator Carol Rushin wrote that the rule provides “inappropriate discretion” when calculating pollution levels.

Wenzler said the EPA is only saying that a decision on the change will come by the end of the year. His organization will file a petition for reconsideration if the change is approved, virtually ensuring the final decision would then rest with the incoming Obama administration. The Obama administration may just decide to scrap the change on its own, depending on when it’s published with the Federal Register. A third option would be for Congress to kill it under the Congressional Review Act.

“I’m pretty confident that this rule will never see the light of day,” said Wenzler, whose organization estimates the change would clear the way for more than two dozen coal-fired power plants within 186 miles of 10 national parks.

![]() Comment on "National parks, including Colorado's Mesa Verde, could be battling brown clouds" using the form below

Comment on "National parks, including Colorado's Mesa Verde, could be battling brown clouds" using the form below